- Home

- Stanley G. Weinbaum

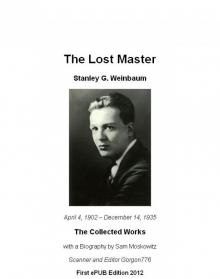

The Lost Master - The Collected Works

The Lost Master - The Collected Works Read online

Introduction

Biography

Dawn of Fame: The Career of Stanley G Weinbaum by Sam Moskowitz

Novels

The New Adam (1939)

The Dark Other (1950)

Short Fiction

The Mad Moon (1934)

Valley of Dreams (1934)

A Martian Odyssey (1934)

The Red Peri (1935)

Flight on Titan (AKA A Man, A Maid, and Saturn's Temptation)(1935)

Parasite Planet (1935)

The Lotus Eaters (1935)

The Planet of Doubt (1935)

The Adaptive Ultimate (1935) [as by John Jessel ]

Pygmalion's Spectacles (1935)

The Worlds of If (1935)

The Ideal (1935)

The Challenge Beyond (1935) (with Murray Leinster, Howard E. Smith, Harl Vincent and Donald Wandrei)

Smothered Seas (1936) with Ralph Milne Farley

Redemption Cairn (1936)

Proteus Island (1936)

The Brink of Infinity (1936)

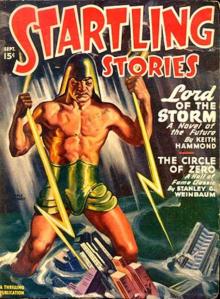

The Circle of Zero (1936)

The Point of View (1936)

Graph (1936)

Dawn of Flame (1936)

Shifting Seas (1937)

Revolution of 1950 (AKA The Dictator) (1938) with Ralph Milne Farley

Tidal Moon (1938) with Helen Weinbaum

The Black Flame (1939)

Non-Genre Fiction

The Lady Dances (novel) (1934) [as by Marge Stanley]

Yellow Slaves (Short Fiction) (1936) with Ralph Milne Farley

The Green Glow of Death (Short Fiction) (1957)

Poems

The Last Martian (1974)

The River (1976)

Essays

An Autobiographical Sketch of Stanley G. Weinbaum (1935)

Unpublished

What's It All About? (novel) (AKA New Lives for Old AKA Utopia Bound) with Edward N. Schoolman, M.D.

The Lady in the Rain (novel)

She Tried to be Bad (short fiction, 6,000 words) [as by Marge Stanley]

Without Love (novel) [as by Marge Stanley]

After Dinner Love (novel) [as by Marge Stanley]

The World's Luckiest (novel) (only a 5 page fragment still exists)

Introduction

Welcome to Volume 7 of the Lost Masters. This collection contains all of the published fiction of Stanley G. Weinbaum, with the exception of one poem. At least, all of the published fiction I could confirm existed.

As usual, the bibliography was compiled from many different sources, and is as complete as I could make it. If you are aware of anything published, or even written, by Weinbaum that is not listed here, please let me know at [email protected].

Unless more of his work turns up, there likely won’t be an update to this collection (other than the one poem that isn’t here).

Enjoy.

Gorgon776

A Word From The Publisher

Without Gorgon776's tremendous work in gathering, scanning, OCRing and HTMLizing the source material, this collection would not be possible. Because of his preparation, other than the need to rename embedded images, conversion to ePUB was relatively easy.

For this edition, we have added Sam Moskowitz's biography of Stanley G. Weinbaum. If you have any questions of comments please visit my Rarities section on Demonoid at http://www.demonoid.me/files/?uid=483111

Amontoth

DAWN OF FAME: The Career of Stanley G. Weinbaum

By SAM MOSKOWITZ

The economic blackness of the Depression hung like a pall over the spirit of America. The year was 1934 and even though many may have desired the temporary escape which science fiction provided, they frequently could not afford to purchase more than a monthly magazine or two.

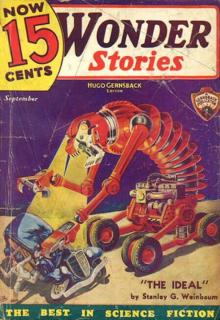

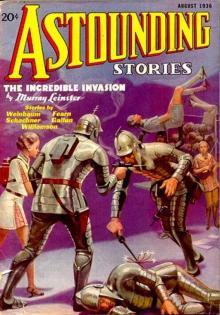

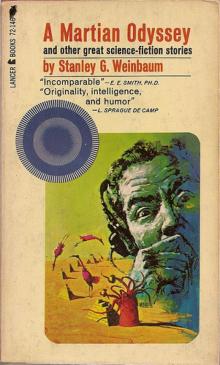

In such an atmosphere, publishers of the three surviving science fiction magazines competed desperately for a diminishing pool of readers. Wonder Stories, Hugo Gernsback's current venture in an exclusively science fiction magazine, gave preference to stories with new ideas and unusual approaches to the worlds of tomorrow. In this, it was joined in grim competition with Astounding Stories. This magazine, after a nine-month lapse in 1933, had been purchased by Street & Smith, and it also featured new and startling ideas, labeling its most unorthodox stories "thought variants." Though harried by financial difficulties, Gernsback humored his teen-age editor, Charles D. Hornig, and took time out to read a short story which had just come in the mail. Publisher and editor, displaying remarkable restraint considering their mutual enthusiasm, wrote in the blurb for A Martian Odyssey by unknown Stanley G. Weinbaum in the July 1934 issue of Wonder Stories: "Our present author ... has written a science fiction tale so new, so breezy, that it stands out head and shoulders over similar interplanetarian stories."

Readers were unreserved in their enthusiasm. The torrent of praise reached such proportions that Hornig, in reply to a reader's ecstatic approval, revealed: "Weinbaum's story has already received more praise than any story in the history of our publication."

This statement was no small thing, for even in 1934 Wonder Stories had a star-studded five-year history which included outstanding tales by John Taine, Jack Williamson, Clifford D. Simak, David H. Keller, Ray Cummings, John W. Campbell, Jr., Stanton A. Coblentz, Clark Ashton Smith, Edmond Hamilton, Robert Arthur, H. P. Lovecraft (a revision of the work of Hazel Heald), and dozens of other names which retain much of their magic, even across the years.

Told in one of the most difficult of narrative techniques, that of the flash-back, A Martian Odyssey was in all respects professionally adroit. The style was light and jaunty, without once becoming farcical, and the characterizations inspiredly conceived throughout. A cast of alien creatures that would have seemed bizarre for The Wizard of Oz was somehow brought into dramatic conflict on the red sands of Mars in a wholly believable manner by the stylistic magic of this new author.

It was Weinbaum's creative brilliance in making strange ventures seem as real as the characters in David Copperfield that impressed readers most. Twe-er-r-rl, the intelligent Martian, an ostrich-like alien with useful manipular appendages —obviously heir of an advanced technology—is certainly one of the truly great characters in science fiction.

The author placed great emphasis on the possibility that so alien a being would think differently from a human being and therefore perform actions which would seem paradoxical or completely senseless to us. This novel departure gave a new dimension to the interplanetary "strange encounter" tale. Tweer-r-r1 was not the only creature to whom difficult-to-understand psychology was applicable. In A Martian Odyssey there was also the silicon monster, who lived on sand, excreting bricks as a by-product and using them to build an endless series of pyramids; round four-legged creatures, with a pattern of eyes around their circumference, who spent their entire lives wheeling rubbish to be crushed by a giant wheel which occasionally turned traitor and claimed one of them instead; and a tentacled plant which lured its prey by hypnotically conjuring up wish-fulfillment images.

How thousands of readers felt about Stanley G. Weinbaum can best be summed up by quoting H. P. Lovecraft, one of the great masters of fantasy.

I saw with pleasure that someone had at last escaped the sickening hackneyedness in which 99.99% of all pulp interplanetary stuff is engulfed. Here, I rejoiced, was somebody who could think of another planet in terms of something besides anthropomorphic kings and beautiful princesses and battles of space ships and ray-guns and attacks from the hairy sub-men of the "dark side" or "polar cap" region, etc., etc. Somehow he had the imagination to envisage wholly alien situations and psychologies and entities, to devise consistent events from wholly al

ien motives and to refrain from the cheap dramatics in which almost all adventure-pulpists wallow. Now and then a touch of the seemingly trite would appear—but before long it would be obvious that the author had introduced it merely to satirize it. The light touch did not detract from the interest of the tales—and genuine suspense was secured without the catchpenny tricks of the majority. The tales of Mars, I think, were Weinbaum's best —those in which that curiously sympathetic being "Tweel" figure.

Too frequently, authors who cause a sensation with a single story are characterized as having come "out of nowhere." Weinbaum's ability to juggle the entire trunkful of standard science fiction gimmicks and come up with something new was not merely a matter of talent. It was grounded in high intelligence, an excellent scientific background, and, most important of all, a thorough knowledge of the field. Weinbaum had read science fiction since the first issue of Amazing Stories in 1926. Before that he had devoured Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, Edgar Allan Poe, Jules Veme, H. G. Wells, A. Conan Doyle, and Edgar Rice Burroughs, as well as many of the great utopian writers.

A graduate chemical engineer, Stanley G. Weinbaum left that field in his early twenties, to try his hand at fiction. His first successful tale was a romantic sophisticated novel, The Lady Dances, which was syndicated by King Features in the early 1930s under the pen name of Marge Stanley, a combination of his wife's name with his own because he felt that a woman's byline would be more acceptable on that kind of story.

Several other experimental novels were written during this period, including two that were science fiction: The Mad Brain and The New Adam. He also turned out an operetta, Omar, the Tent Maker, with the music written by his sister, Helen Weinbaum Kasson; a short story, Real and Imaginary; and a short-short, Graph. None of these was ever submitted to a fantasy periodical during his lifetime. The operetta has never been published or produced. A sheaf of poetry dating from this period must be in existence, judging by the manner in which he interspersed verse into the text of almost all of his novels. Weinbaum must have turned to writing because he was a creative artist with an overwhelming urge to write, for certainly, as a means of earning a livelihood during the Depression, science fiction was not rewarding. He was thirty-two years old when A Martian Odyssey appeared in Wonder Stories and the sum he received for the story, at the prevailing rates, could scarcely have exceeded $55. Over at Street & Smith, Desmond Hall, as assistant to F. Orlin Tremaine, read the tale and was greatly impressed. He prevailed upon Julius Schwartz, then the only literary agent specializing in science fiction, to see what he could do about getting some Weinbaum material for Astounding Stories. Schwartz was also editor of Fantasy Magazine, a science fiction fan publication, as well as a partner in the Solar Sales Service with his close friend, Mort Weisinger. He had entry to all editorial offices. The problem now was how to obtain Weinbaum's address.

"Everyone believes that Weinbaum is a pen name for a well-known author," he ventured to Hornig of Wonder Stories.

"You mean Ralph Milne Farley?" Hornig queried, after checking his files and noting that both Weinbaum and Farley lived in Milwaukee. His expression was noncommittal. "What address did Farley use?" Schwartz asked, hoping that Hornig would be reasonably cooperative. "3237 North Oakland Avenue," Hornig replied.

That was all Schwartz needed to know. He wrote Weinbaum and offered to handle his work. Weinbaum agreed and sent him a new short story, The Circle of Zero. It was turned down by every magazine in the field, but an agent-author relationship was formed that was to endure long after Weinbaum's death and become a major factor in the perpetuation of his fame.

Anxious to capitalize upon the popularity of A Martian Odyssey, Homig urged Weinbaum to write a sequel. Weinbaum agreed and then played a strangely acceptable trick upon his readers. An earlier draft of A Martian Odyssey had been titled Valley of Dreams. Weinbaum found that, with a few additions and a little rewriting, it would serve magnificently as a sequel. He made the changes and sent the story to Wonder Stories. The story appeared in the November 1934 issue and if the readers suspected they were being entertained by the same story twice you couldn't tell it from their letters. Despite the intervention of the intrepid Julius Schwartz, Wonder Stories might have kept Weinbaum on an exclusive basis a while longer had it not been for an overexacting editonal policy. Weinbaum had submitted Flight on Titan, a novelette speckled with such strange life forms as knife kites, ice ants, whiplash trees, and threadworms. It was not up to the level of the Odyssey stories, but was considerably superior to the general level of fiction Hornig was running at the time. Nevertheless, it was rejected because it did not contain a "new" idea and Schwartz, toting it like a football around end, scored a touchdown at Astounding Stories. The story was instantly accepted. Parasite Planet, which appeared in Astounding Stories for March 1935, the month after Flight on Titan, was the first of a trilogy featuring Ham Hammond and Patricia Burlingame. Though this story was merely a light romantic travelogue, the slick handling of the excursion across Venus with its Jack Ketch Trees which whirled lassos to catch their food; doughpots, mindless omnivorous masses of animate cells, and the Cyclops-like, semi-intelligent mops noctivans, charmed the readers with a spell reminiscent of Martian Odyssey.

In a sense, all of Weinbaum's stories were one with Homer's Odyssey, inasmuch as they were fundamentally alien-world travel tales. The plot of each was a perilous quest. Beginning with his tales in Astounding Stories, Weinbaum introduced a maturely shaded boy-meets-girl element, something brand new to the science fiction of 1935, and he handled it as well as the best of the women's-magazine specialists. The wonderful noted creatures he invented were frosting on the cake, an entirely irresistible formula.

To all this Weinbaum now added a fascinating dash of philosophy with The Lotus Eaters, a novelette appearing in the April 1935 Astounding Stories and unquestionably one of his most brilliant masterpieces. On the dark side of Venus, Ham and Pat meet a strange cavern-dwelling creature, actually a warm-blooded planet, looking like nothing so much as an inverted bushel basket, whom they dub Oscar. Intellectually almost omnipotent, Oscar is able to arrive at the most astonishingly accurate conclusions about his world and the universe by extrapolating from the elementary exchanges of information. Despite his intelligence, Oscar has no philosophical objection to being eaten by the malevolent trioptm, predatory marauders of his world.

The entire story is nothing more than a series of questions and answers between the lead characters and Oscar, yet the reader becomes so absorbed that he might very easily imagine himself to be under the influence of the narcotic spores which are responsible for the Venusian's pontifical inertia. Economic considerations as well as loyalty to the magazine which had published his first important science fiction story required that Weinbaum continue to consider Wonder Stories as a market, despite its low word rates. Realizing that the magazine was reluctant to publish any story that did not feature a new concept, he gave the editors what they wanted, selling in a single month, December 5934, three short stories, Pygmalion's Spectacles, The Worlds of If, and The Ideal. The first, appearing in the June 1935 Wonder Stories, centers about the invention of a new type of motion picture, where the viewer actually thinks he is participating in the action. The motion picture involves a delightful boy-meets-girl romance, ending when the viewer comes awake from the hypnotic effect of the film to team that he has participated in a fantasy. All is happily resolved when he finds that the feminine lead was played by the inventor's daughter and romance is still possible. The Worlds of If was the first of a series of three stories involving Professor van Manderpootz, an erratic bearded scientist, and young Dixon Wells, who is always late and always sorry. The plot revolves about a machine that will show the viewer what would have happened if he had—married a woman other than his wife; not gone to college; flunked his final exams, or taken that other job. The humor is broad and the plotting a bit too synoptic to be effective.

The second story in the series, The Ideal, has for its theme the b

uilding of a machine which will reveal a man's mental and emotional orientation to reality through a systematic exploration of his subconscious motives.

The final story, The Point of View, is based on the imaginative assumption that, through the use of an even more remarkable machine—an "attitudinizer"—one can see the world through the minds of others. The three stories arc almost identical, varied only by the nature of the invention itself. There is a striking similarity in theme and characterization between this story and Erckmann-Chatrian's short story Hans Schnap's Spy Class—even to the use of the term "point of view"—which appeared in the collection The Bells; or, The Polish Jew, published in England in 1870.

Despite their slightness, the van Manderpootz tales are important because fascinating philosophical speculations accompany each description of a mechanical gimmick. Enlivened by humor and carried easily along on a high polish, Weinbaum's style now effectively disguised the fact that a philosopher was at work.

Understandably gaining confidence with success, Weinbaum embarked on a more ambitious writing program. He began work on a short novel, the 25,000-word Dawn of Flame, featuring a woman of extraordinary beauty, Black Margot, and stressing human characterization and emotional conflict. A disappointment awaited him, however. The completed novel went the rounds of the magazines and was rejected as not being scientific or fantastic enough.

The Complete Margaret of Urbs

The Complete Margaret of Urbs The Black Flame

The Black Flame The New Adam

The New Adam Dawn of Flame

Dawn of Flame The Ideal

The Ideal Proteus Island

Proteus Island The Worlds of If

The Worlds of If The Lost Master - The Collected Works

The Lost Master - The Collected Works The 27th Golden Age of Science Fiction

The 27th Golden Age of Science Fiction A Martian Odyssey

A Martian Odyssey Valley of Dreams

Valley of Dreams The Point of View

The Point of View The Circle of Zero

The Circle of Zero