- Home

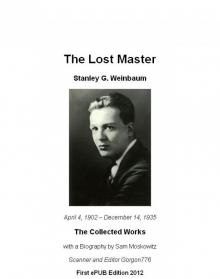

- Stanley G. Weinbaum

The Complete Margaret of Urbs

The Complete Margaret of Urbs Read online

Jerry eBooks

No copyright 2017 by Jerry eBooks

No rights reserved. All parts of this book may be reproduced in any form and by any means for any purpose without any prior written consent of anyone.

Margaret of Urbs

The Complete Stories

Stanley G. Robinson

(custom book cover)

Jerry eBooks

Original Publication Information

The Story Behind Dawn of Flame and The Black Flame

A Tribute to Stanley G. Weinbaum

THE BLACK FLAME

DAWN OF FLAME

THE BLACK FLAME

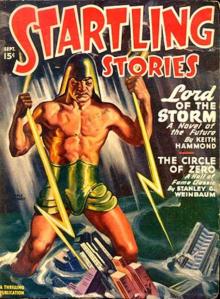

Startling Stories

January, 1939

Volume I, Number 1

DAWN OF FLAME

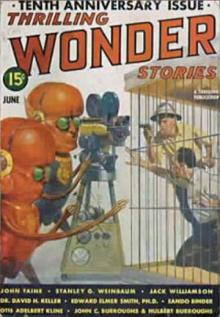

Thrilling Wonder Stories

June, 1939

Volume XIII, Number 3

“The Story Behind The Black Flame and Dawn of Flame”

Fantastic Story Magazine

Spring, 1952

Volume 3, Number 3

Custom eBook created by

Jerry eBooks

December 2017

The Story Behind

DAWN OF FLAME

and

THE BLACK FLAME

BROUGHT together here as they belong are the two long related stories frequently considered Stanley G. Weinbaurn’s best works. Though THE BLACK FLAME was written first and was followed about six months later by DAWN OF FLAME, in the actual chronology of fictional events DAWN comes first. We have therefore set them up so. in order that you may read the full story in its proper order and sequence.

A premature death cut short Stanley Weinbaum’s career just as it was flowering into maturity. He was a man of colossal mental activity, constantly bubbling with ideas to winch he gave the fresh and original twists which are the product of a highly sophisticated mind. His admirers are vociferously loyal and possess tenacious memories, so that sixteen years after his death the requests for his stories are as unremitting as ever.

Most of his fans feel exactly as did the one who wrote us recently to say that had Weinbaum lived, his genius would have far outclassed that of any science-fiction writer living today.

There is no doubt that Weinbaum’s stories abound with flashes of genius. Moreover, his versatility was amazing. THE BRINK OF INFINITY was a story dealing with pure mathematics—and which managed to make that dry science fascinating—while the FLAME stories are high romantic adventure. Yet in spite of the diametrically opposed themes, both become completely absorbing under the magic of Stanley G. Weinbaum’s touch.

It is something of a public service, therefore, to respond to so many thousands of requests and bring you the two FLAME stories. To us it is something of a gesture toward remembering a brilliant youth whose death was a loss and who deserves to be remembered. If you have read Weinbaum before, you will treasure these stories. If he is new to you, after reading them you may better understand the fierce loyalty which surrounds his memory.

To few people is given the ability of foreseeing the eventual value of things in their own time, so that many of the early classics now out of print, have become scarce or unavailable altogether. Thousands of new leaders who are discovering science fiction every year have never read Weinbaum and might never have the opportunity of doing so were the stories not brought to light again.

And if there is someone you know who has expressed curiosity about science fiction and you have been wondering what to give him to start, you could do worse than to start him right here!

—The Editor

A Tribute to

the Late

STANLEY G. WEINBAUM

Author of “The Black Flame”

By

OTTO BINDER

Popular Author of Many Science Fiction Novels and Stories

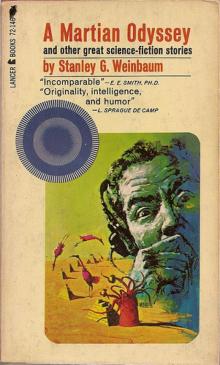

A MARTIAN ODYSSEY, his first science fiction story, brought Stanley G. Weinbaum instant recognition. Who can forget the amazing, lovable “Twe-e-r-r-rl” ? It was only the first of many fascinating creatures of other worlds—master-mind Oscar of the Lotus-Eaters, the pathetically dumb Loonies, the demoniac Trioptes . . . He brought them to life with a deft, masterful touch.

His human characters were lifelike and colorful—Van Manderpootz, acid-tongued and so modest, Dixon Wells, always late and always sorry, the Red Peri, Queen of the Spaceways, and others.

Weinbaum wove these creatures and characters into story situations that held suspense from the first to the last word.

It is amazing to me, as an author, how Weinbaum could produce, in steady succession, stories of such excellent composition and originality. Worlds of If was, and perhaps still is, the best exposition to date of the multiple-universe idea. Circle of Zero breathed the true, chilling atmosphere of the “unending-world” theory. His Brink of Infinity was the only story that ever made pure, dry mathematics an engrossing theme.

A MODEL OF SIMPLICITY

Weinbaum’s style of writing has been a model of simplicity and sincerity never since duplicated by other authors in our field. If story-telling is a “gift,” Weinbaum had it. I believe, personally, that if he had lived, he would eventually have earned a place alongside such masters of fantasy as Verne, Wells, Merritt and Burroughs.

One had only to meet Weinbaum to appreciate why he wrote good stories. I visited him in Milwaukee, one summer’s day, and passed one of the most interesting afternoons of my life. His reading knowledge of science was tremendous and up-to-date. His fund of new story-ideas seemed exhaustless. His imagination was powerful.

UNBOUNDED ENTHUSIASM

But most of all, Weinbaum had an unbounded enthusiasm for science fiction. In the last analysis, I think it is that quality that shines through his work and gives it its inimitable appeal. Weinbaum honestly put his heart and soul into his writing. He was not above a little satire at times, but always with a core of sincerity behind it all.

We talked of many things that afternoon, but particularly of the future of science fiction.

Weinbaum predicted that science fiction would or should soon pass out of its phase of stilted “classical” form, and into a phase stressing human interest and realistic style of presentation. He has been right. Weinbaum himself was not the least of the forces that molded this change for the better in science fiction.

A REAL LOSS

Weinbaum’s death was a real loss to science fiction. He had set a pace that made the rest of us writers sit up and take notice. He was leading the way to new, untouched heights in creativeness. And science fiction benefited.

It is a fitting commentary on Weinbaum’s work that, three years after his death, his writings are still being published.

I feel that the editors of STARTLING STORIES are paying a fine tribute to his memory in presenting this story, “The Black Flame”.

It comes close, in my opinion, to being the “masterpiece” of Weinbaum’s facile pen.

CHAPTER I

Penalty—and Aftermath

THOMAS MARSHALL CONNOR was about to die. The droning voice of the prison chaplain gradually dulled his perception instead of stimulating his mind. Everything was hazy and indistinct to the condemned man. He was going to the electric chair in just ten minutes to pay the supreme penalty because he had accidentally killed a man with his bare fists.

Connor, vibrantly alive, vigorous and healthy, only twenty-six, a brilliant young engineer, was going to die. And, knowing, he did not care. But there was nothing at all nebulous about the gray stone and cold iron bars of the death cell. There was nothing uncertain about the split down his trouser leg and the shaven spot on his head.

The condemned man was acutely aware of the solidarity of material things about him. The wo

rld he was leaving was concrete and substantial. The approaching footsteps of the death guard sounded heavily in the distance.

Then the cell door opened, and the chaplain ceased his murmuring. Passively Thomas Marshall Connor accepted his blessings, and calmly took his position between his guards for his last voluntary walk.

He remained in his state of detachment as they seated him in the chair, strapped his body and fastened the electrodes. He heard the faint rustling of the witnesses and the nervous, rapid scratching of reporters’ pencils. He could imagine their adjectives—“Calloused murderer” . . . “Brazenly indifferent to his fate.”

But it was as if the matter concerned a third party.

He simply relaxed and waited. To die so quickly and painlessly was more a relief than anything. He was not even aware when the warden gave his signal. There was a sudden silent flash of blue light. And then—nothing at all.

* * * * *

SO this was death. The slow and majestic drifting through the Stygian void, borne on the ageless tides of eternity.

Peace, at last—peace, and quiet, and rest.

But what was this sensation like the glimpse of a faint, faraway light which winked on and off like a star? After an interminable period the light became fixed and steady, a thing of annoyance. Thomas Marshall Connor slowly became aware of the fact of his existence as an entity, in some unknown state. The senses and memories that were his personality struggled weakly to reassemble themselves into a thinking unity of being—and he became conscious of pain and physical torture.

There was a sound of shrill voices, and a stir of fresh air. He became aware of his body again. He lay quiet, inert, exhausted. But not as lifeless as he had lain for—how long?

When the shrill voices sounded again, Connor opened unseeing eyes and stared at the blackness just above him. After a space he began to see, but not to comprehend. The blackness became a jagged, pebbled roof no more than twelve inches from his eyes—rough and unfinished like the under side of a concrete walk.

The light became a glimmer of daylight from a point near his right shoulder.

Another sensation crept into his awareness. He was horribly, bitterly cold. Not with the chill of winter air, but with the terrible frigidity of inter-galactic space. Yet he was on—no, in, earth of some sort. It was as if icy water flowed in his veins instead of blood. Yet he felt completely dehydrated. His body was as inert as though detached from his brain, but he was cruelly imprisoned within it. He became conscious of a growing resentment of this fact.

Then, stimulated by the shrilling, piping voices and the patter of tiny feet out there somewhere to the right, he made a tremendous effort to move. There was a dry, withered crackling sound—like the crumpling of old parchment—but indubitably his right arm had lifted!

The exertion left him weak and nauseated. For a time he lay as in a stupor. Then a second effort proved easier. After another timeless interval of struggling torment his legs yielded reluctant obedience to his brain. Again he lay quietly, exhausted, but gathering strength for the supreme effort of bursting from his crypt.

For he knew now where he was. He lay in what remained of his grave. How or why, he did not know. That was to be determined.

With all his weak strength he thrust against the left side of his queer tomb, moving his body against the crevice at his right. Only a thin veil of loose gravel and rubble blocked the way to the open. As his shoulder struck the pile, it gave and slid away, outward and downward, in a miniature avalanche.

Blinding daylight smote Connor like an agony. The shrill voices screamed.

“ ’S moom!” a child’s voice cried tremulously. “ ’S moom again!”

Connor panted from exertion, and struggled to emerge from his hole, each movement producing another noise like rattling paper. And suddenly he was free! The last of the gravel tinkled away and he rolled abruptly down a small declivity to rest limply at the bottom of the little hillside.

HE saw now that erosion had cut through this burial ground—wherever it was—and had opened a way for him through the side of his grave. His sight was strangely dim, but he became aware of half a dozen little figures in a frightened semicircle beyond him.

Children! Children in strange modernistic garb of bright colors, but nevertheless human children who stared at him with wide-open mouths and popping eyes. Their curiously cherubic faces were set in masks of horrified terror.

Suddenly recalling the terrors he had sometimes known in his own childhood, Connor was surprised they did not flee. He stretched forth an imploring hand and made a desperate effort to speak. This was his first attempt to use his voice, and he found that he could not.

The spell of dread that held the children frozen was instantly broken. One of them gave a dismayed cry: “A-a-a-h! ’S a specker!”

In panic, shrieking that cry, the entire group turned and fled. They disappeared around the shoulder of the eroded hill, and Connor was left horribly alone. He groaned from the depths of his despair and was conscious of a faint rasping noise through his cracked and parched lips.

He realized suddenly that he was quite naked—his shroud had long since moldered to dust. At the same moment that full comprehension of what this meant came to him, he was gazing in horror at his body. Bones! Nothing but bones, covered with a dirty, parchmentlike skin!

So tightly did his skin cover his skeletal framework that the very structure of the bones showed through. He could see the articulation at knuckles, knees, and toes. And the parchment skin was cracked like an ancient Chinese vase, checked like aged varnish. He was a horror from the tomb, and he nearly fainted at the realization.

After a swooning space, he endeavored to arise. Finding that he could not, he began crawling painfully and laboriously toward a puddle of water from the last rain. Reaching it, he leaned over to place his lips against its surface, reckless of its potability, and sucked in the liquid until a vast roaring filled his ears.

The moment of dizziness passed. He felt somewhat better, and his breathing rasped a bit less painfully in his moistened throat. His eyesight was slowly clearing and, as he leaned above the little pool, he glimpsed the specter reflected there. It looked like a skull—a face with lips shrunken away from the teeth, so fleshless that it might have been a death’s head.

“Oh, God!” he called out aloud, and his voice croaked like that of a sick raven. “What and where am I!”

In the back of his mind all through this weird experience, there had been a sense of something strange aside from his emergence from a tomb in the form of a living scarecrow. He stared up at the sky.

THE vault of heaven was blue and fleecy with the whitest of clouds. The sun was shining as he had never thought to see it shine again. The grass was green. The ground was normally earthy. Everything was as it should be—but there was a strangeness about it that frightened him. Instinctively he knew that something was direfully amiss.

It was not the fact that he failed to recognize his surroundings. He had not had the strength to explore; neither did he know where he had been buried. It was that indefinable homing instinct possessed in varying degree by all animate things.

That instinct was out of gear. His time sense had stopped with the throwing of that electric switch—how long ago? Somehow, lying there under the warming rays of the sun, he felt like an alien presence in a strange country.

“Lost!” he whimpered like a child.

After a long space in which he remained in a sort of stupor, he became aware of the sound of footsteps. Dully he looked up. A group of men, led by one of the children, was advancing slowly toward him. They wore brightly colored shirts—red, blue, violet—and queer baggy trousers gathered at the ankles in an exotic style.

With a desperate burst of energy, Connor gained his knees. He extended a pleading, skeletonlike claw.

“Help me!” he croaked in his hoarse whisper.

The beardless, queerly effeminate-looking men halted and stared at him in horror.

“ ’Assim!” shrilled the child’s voice. “ ’S a specker. ’S dead.”

One of the men stepped forward, looking from Connor to the gaping hole in the hillside.

“Wassup?” he questioned.

Connor could only repeat his croaking plea for aid.

“’Esick,” spoke another man gravely. “Sleeper, eh?”

There was a murmur of consultation among the men with the bright clothes and oddly soft, womanlike voices.

“T’ Evanie!” decided one. “T’ Evanie, the Sorc’ess.”

They closed quickly around the half reclining Connor and lifted him gently. He was conscious of being borne along the curving cut to a yellow country road, and then black oblivion descended once more to claim him.

When he regained consciousness the next time, he found that he was within walls, reclining on a soft bed of some kind. He had a vague dreamy impression of a girlish face with bronze hair and features like Raphael’s angels bending over him. Something warm and sweetish, like glycerin, trickled down his throat.

Then, to the whispered accompaniment of that queerly slurred English speech, he sank into the blissful repose of deep sleep.

CHAPTER II

Evanie the Sorceress

THERE were successive intervals of dream and oblivion, of racking pain and terrible nauseating weakness; of voices murmuring queer, unintelligible words that yet were elusively familiar.

Then one day he awoke to the consciousness of a summer morning. Birds twittered; in the distance children shouted. Clear of mind at last, he lay on a cushioned couch puzzling over his whereabouts, even his identity, for nothing within his vision indicated where or who he was.

The first thing that caught his attention was his own right hand. Paper-thin, incredibly bony, it lay like the hand of death on the rosy coverlet, so transparent that the very color shone through. He could not raise it; only a twitching of the horrible fingers attested its union with his body. The room itself was utterly unfamiliar in its almost magnificently simple furnishings. There were neither pictures nor ornaments. Only several chairs of aluminumlike metal, a gleaming silvery table holding a few ragged old volumes, a massive cabinet against the opposite wall, and a chandelier pendant by a chain from the ceiling.

The Complete Margaret of Urbs

The Complete Margaret of Urbs The Black Flame

The Black Flame The New Adam

The New Adam Dawn of Flame

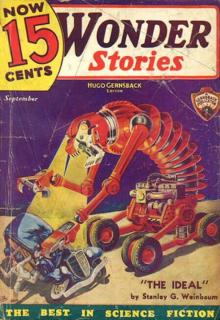

Dawn of Flame The Ideal

The Ideal Proteus Island

Proteus Island The Worlds of If

The Worlds of If The Lost Master - The Collected Works

The Lost Master - The Collected Works The 27th Golden Age of Science Fiction

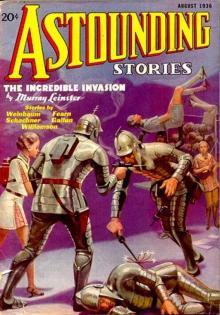

The 27th Golden Age of Science Fiction A Martian Odyssey

A Martian Odyssey Valley of Dreams

Valley of Dreams The Point of View

The Point of View The Circle of Zero

The Circle of Zero