- Home

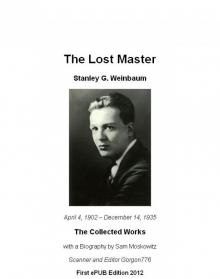

- Stanley G. Weinbaum

The Complete Margaret of Urbs Page 2

The Complete Margaret of Urbs Read online

Page 2

He tried to call out. A faint croak issued.

The response was startlingly immediate. A soft voice said, “Hahya?” in his ear and he turned his head painfully to face the girl of the bronze hair, seated at his side. She smiled gently.

She was dressed in curious green baggy trousers gathered at the ankle, and a brilliant green shirt. She had rolled the full sleeves to her shoulders. Hers was like the costume of the men who had brought him here.

“Whahya?” she said softly.

He understood.

“Oh! I’m—uh—Thomas Connor, of course.”

“Thomas Connor, of course?” she echoed.

He smiled feebly.

“No. Just Thomas Connor.”

“F’m ’ere?”

“From St. Louis.”

“Selui? ’S far off.”

Far off? Then where was he? Suddenly a fragment of memory returned. The trial—Ruth—that catastrophic episode of the grim chair. Ruth! The yellow-haired girl he had once adored, who was to have been his wife—the girl who had coldly sworn his life away because he had killed the man she loved.

Dimly memory came back of how he had found her in that other man’s arms on the very eve of their wedding; of his bitter realization that the man he had called friend had stolen Ruth from him. His outraged passions had flamed, the fire had blinded him, and when the ensuing battle had ended, the man had been crumpled on the green sward of the terrace, with a broken neck.

He had been electrocuted for that. He had been strapped in that chair!

Then—then the niche on the hill.

But how—how? Had he by some miracle survived the burning current? He must have—and he still had the penalty to pay!

He tried desperately to rise.

“Must leave here!” he muttered. “Get away—must get away.” A new thought. “No! I’m legally dead. They can’t touch me now; no double jeopardy in this country. I’m safe!”

VOICES sounded in the next room, discussing him.

“F’m Selui, he say,” said a man’s voice. “Longo, too.”

“Eah,” said another. “ ’S lucky to live—lucky! ’L be rich.”

That meant nothing to him. He raised his hand with a great effort; it glistened in the light with an oil of some sort. It was no longer cracked, and the ghost of a layer of tissue softened the bones. His flesh was growing back.

His throat felt dry. He drew a breath that ended in a tickling cough.

“Could I have some water?” he asked the girl.

“N-n-n!” She shook her head. “N’ water. S’m licket?”

“Licket?” Must be liquid, he reflected. He nodded, and drank the mug of thick fluid she held to his lips.

He grinned his thanks, and she sat beside him. He wondered what sort of colony was this into which he had fallen—with their exotic dress and queer, clipped English.

His eyes wandered appreciatively over his companion; even if she were some sort of foreigner, she was gloriously beautiful, with her bronze hair gleaming above the emerald costume.

“C’n talk,” she said finally as if in permission.

He accepted. “What’s your name?”

“ ’M Evanie Sair. Evanie the Sorc’ess.”

“Evanie the Sorceress!” he echoed. “Pretty name—Evanie. Why the Sorceress, though? Do you tell fortunes?”

The question puzzled her.

“N’onstan,” she murmured.

“I mean—what do you do?”

“Sorc’y.” At his mystified look, she amplified it. “To give strength—to make well.” She touched his fleshless arm.

“But that’s medicine—a science. Not sorcery.”

“Eah. Science—sorc’y. ’S all one. My father, Evan Sair the Wizard, taught me.” Her face shadowed. “ ’S dead now.” Then, abruptly: “Whe’s your money?” she asked.

He stared. “Why—in St. Louis. In a bank.”

“Oh!” she exclaimed. “N-n-n! Selui! N’safe!”

“Why not?” He started. “Has there been another flood of bank-bustings?”

The girl looked puzzled.

“N’safe,” she reiterated. “Urbs is better. For very long, Urbs is better.” She paused. “When’d you sleep?”

“Why, last night.”

“N-n-n. The long sleep.”

The long sleep! It struck him with stunning force that his last memories before that terrible awakening had been of a September world—and this was mid-summer! A horror gripped him. How long—how long—had he lain in his—grave? Weeks? No—months, at least.

He shuddered as the girl repeated gently, “When?”

“In September,” he muttered.

“What year?”

Surprise strengthened him. “Year? Nineteen thirty-eight, of course!” She rose suddenly. “ ’S no Nineteen thirty-eight. ’S only Eight forty-six now!”

THEN she was gone, nor on her return would she permit him to talk. The day vanished; he slept, and another day dawned and passed. Still Evanie Sair refused to allow him to talk again, and the succeeding days found him fuming and puzzled. Little by little, however, her strange clipped English became familiar.

So he lay thinking of his situation, his remarkable escape, the miracle that had somehow softened the discharge of Missouri’s generators. And he strengthened. A day came when Evanie again permitted speech, while he watched her preparing his food.

“Y’onger, Tom?” she asked gently. “ ’L bea soon.” He understood; she was saying, “Are you hungry, Tom? I’ll be there soon.”

He answered with her own affirmative “Eah,” and watched her place the meal in a miraculous cook stove that could be trusted to prepare it without burning.

“Evanie,” he began, “how long have I been here?”

“Three months,” said Evanie. “You were very sick.”

“But how long was I asleep?”

“You ought to know,” retorted Evanie. “I told you this was Eight forty-six.”

He frowned.

“The year Eight forty-six of what?”

“Just Eight forty-six,” Evanie said matter of factly. “Of the Enlightenment, of course. What year did you sleep?”

“I told you—Nineteen thirty-eight,” insisted Connor, perplexed. “Nineteen thirty-eight. A.D.”

“Oh,” said Evanie, as if humoring a child.

Then, “A.D?” she repeated. “Anno Domini, that means. Year of the Master. But the Master is nowhere near nineteen hundred years old.” Connor was nonplussed. He and Evanie seemed to be talking at crosspurposes. He calmly started again.

“Listen to me,” he said grimly. “Suppose you tell me exactly what you think I am—all about it, just as if I were a—oh, a Martian. In simple words.”

“I know what you are,” said Evanie. “You’re a Sleeper. Often they wake with muddled minds.”

“And what,” he pursued doggedly, “is a Sleeper?”

Surprisingly Evanie answered that, in a clear, understandable—but most astonishing—way. Almost as astonished herself that Connor should not know the answer to his question.

“A Sleeper,” she said simply, and Connor was now able to understand her peculiar clipped speech—the speech of all these people—with comparative ease, “is one of those who undertake electrolepsis. That is, have themselves put to sleep for a long term of years to make money.”

“How? By exhibiting themselves?”

“No,” she said. “I mean that those who want wealth badly enough, but won’t spend years working for it, undertake the Sleep. You must remember that—if you have forgotten so much else. They put their money in the banks organized for the Sleepers. You will remember. They guarantee six percent. You see, don’t you? At that rate a Sleeper’s money increases three hundred times a century—three hundred units for each one deposited. Six percent doubles their money every twelve years. A thousand becomes a fortune of three hundred thousand, if the Sleeper outlasts a century—and if he lives.”

“Fairy tales!”

Connor said contemptuously, but now he understood her question about the whereabouts of his money, when he had first awakened. “What institution can guarantee six percent with safety? What could they invest in?”

“They invest in one percent Urban bonds.”

“And run at a loss, I suppose!”

“No. Their profits are enormous—from the funds of the nine out of every ten Sleepers who fail to waken!” slowly. “I wish—you would tell me the truth.”

“So I’m a Sleeper!” Connor

said.

Evanie gazed anxiously down at him.

“Electrolepsis often muddles one,” she murmured.

“I’m not muddled!” he yelled. “I want truth, that’s all. I want to know the date.”

“It’s the middle of July, Eight hundred and forty-six,” Evanie said patiently.

“The devil it is! Perhaps I slept backward then! I want to know what happened to me.”

“Then suppose you tell,” Evanie said gently.

“I will!” he cried frantically. “I’m the Thomas Marshall Connor of the newspapers—or don’t you read ’em? I’m the man who was tried for murder, and electrocuted. Tom Connor of St. Louis—St. Louis! Do you understand?”

EVANIE’S gentle features went suddenly pale.

“St. Louis!” she whispered. “St. Louis—the ancient name of Selui! Before the Dark Centuries—impossible!”

“Not impossible—true,” Connor said grimly. “Too painfully true.”

“Electrocution!” Evanie whispered awedly. “The Ancients’ punishment!”

She stared as if fascinated, then cried excitedly: “Could electrolepsis happen by accident? Could it? But no! A milliampere too much and brain’s destroyed; a millivolt too little and asepsis fails. Either way’s death—but it has happened if what you are telling is the truth, Tom Connor! You must have experienced the impossible!”

“And what is electrolepsis?” Connor asked, desperately calm.

“It—it’s the Sleep!” whispered the tense girl. “Electrical paralysis of the part of the brain before Rolando’s Fissure. It’s what the Sleepers use, but only for a century, or a very little more. This—this is fantastic! You have slept since before the Dark Centuries! Not less than a thousand years!”

CHAPTER III

Forest Meeting

A WEEK—the third since Connor’s awakening to sane thought, had passed. He sat on a carved stone bench before Evanie’s cottage and reveled in the burning canopy of stars and copper moon. He was living, if what he had been told was true—and he was forced to believe it now—after untold billions had passed into eternity.

Evanie must have been right. He was convinced by her gentle insistence, by the queer English on every tongue, by a subtle difference in the very world about him. It wasn’t the same world—quite.

He sighed contentedly, breathing the cool night air. He had learned much of the new age from Evanie, though much was still mysteriously veiled. Evanie had spoken of the city of Urbs and the Master, but only vaguely. One day he asked her why.

“Because”—she hesitated—“well, because it’s best for you to form your own judgments. We—the people around here—are not fond of Urbs and the Immortals, and I would not like to influence you, Tom, for in all truth, it’s the partisans of the Master who have the best of it, not his enemies. Urbs is in power; it will probably remain in power long after our lifetimes, since it has ruled for seven centuries.”

Connor looked at the gentle Evanie.

“I’m sure,” he said, “that your side of the question is mine.”

Abruptly she withdrew something from her pocket and passed it to him. He bent over it—a golden disc, a coin. He made out the lettering “10 Units,” and the figure of a snake circling a globe, its tail in its mouth.

“The Midgard Serpent,” said Evanie. “I don’t know why, but that’s what it’s called.”

Connor reversed the coin. There was revealed the embossed portrait of a man’s head, whose features, even in miniature, looked cold, austere, powerful. Connor read:

“Orbis Terrarum Imperator Dominusque Urbis.”

“Emperor of the World and Master of the City,” he translated.

“Yes. That is the Master.” Evanie’s voice was serious as she took the coin. “This is the money of Urbs. To understand Urbs and the Master you must of course know something of history since your—sleep.”

“History?” he repeated.

She nodded. “Since the Dark Centuries. Some day one of our patriarchs will tell you more than I know. For I know little of your mighty ancient world. It seems to us an incredible age, with its vast cities, its fierce nations, its inconceivable teeming populations, its terrific energies and its flaming genius. Great wars, great industries, great art—and then great wars again.”

“But you can tell me—” Connor began, a little impatiently. Evanie shook her head.

“Not now,” she said quickly. “For now I must hasten to friends who will discuss with me a matter of great moment. Perhaps some day you may learn of that, too.”

And she was gone before Tom Connor could say a word to detain her. He was left alone with his thoughts—clashing, devastating thoughts sometimes, for there was so much to be learned in this strange world into which he had been plunged.

In so many ways it was a strange, new world, Connor thought, as he watched the girl disappear down the road that slanted from her hilltop home to the village. From where he sat on that bench of hewn stone he could glimpse the village at the foot of the hill—a group of buildings, low, of some white stone. All of the structures were classical, with pure Doric columns. Ormon was the name of the village, Evanie had said.

All strange to him. Not only were the people so vastly at variance with those he had known, but the physical world was bewilderingly different.

Gazing beyond the village, and bringing his attention back to the hills and the forests about him, Tom Connor wondered if they, too, would be different.

He had to know.

THE springtime landscape beckoned. Connor’s strength had returned to such an extent that he arose from his bench in the sun and headed toward the green of the forest stretching away behind Evanie’s home. It was an enchanting prospect he viewed. The trees had the glistening new green of young foliage, and emerald green grass waved in the fields that stretched away down the hillsides and carpeted the plains.

Birds were twittering in the trees as he entered the forest—birds of all varieties, in profusion, with gaily-colored plumage. Their numbers and fearlessness would have surprised Connor had he not remembered something Evanie had told him. Urbs, she had said, had wiped out objectionable stinging insects, flies, corn-worms and the like, centuries ago, and the birds had helped. As had certain parasites that had been bred for the purpose.

“They only had to let the birds increase,” Evanie had said, “by destroying their chief enemy—the Egyptian cat; the house-cat. It was acclimatized here and running wild in the woods, so they bred a parasite—the Feliphage—which destroyed it. Since then there have been many birds, and fewer insects.”

It was pleasant to stroll through that green forest, to that bird orchestral accompaniment. The spring breeze touched Tom Connor’s face lightly, and for the first time in his life he knew what it was to stroll in freedom, untouched by the pestiferous annoyance of mosquitoes, swarming gnats and midges, or other stinging insects that once had made the greenwood sometimes akin to purgatory.

What a boon to humanity! Honey bees buzzed in the dandelions in the carpeting grass, and drank the sweetness from spring flowers, but no mites or flies buzzed about Connor’s uncovered, unflung head as he swung along briskly.

Connor did not know how far he had penetrated into the depths of the newly green woods when he found himself following the course of a small stream. Its silvery waters sparkled in the sunlight filtering through the trees as it moved along, lazily somnolent.

Now and then he passed mossy and viny heaps of ston

es, interesting to him, since he knew, from what he had been told, that they were the sole reminders of ancient structures erected before the Dark Centuries. Those heaps of stones had once formed buildings in another, and long-gone age—his own age.

Idly following the little stream, he came at last to a wide bend where the stream came down from higher ground to spill in a little splashing falls.

He had just rounded the bend, his eyes on a clear, still pool beyond, when he stopped stockstill, his eyes widening incredulously.

It was as if he were seeing spread before him a picture, well known in his memory, and now brought to animate life. Connor had thought himself alone in that wood, but he was not. Sharing it with him, there within short yards of where he stood, was the most beautiful creature on whom he had ever looked.

It was hard to believe she was a living, breathing being and not a figment of his imagination. No sound had warned her of his approach and, sublimely unaware that she was not alone, she held the pose in which Connor had first seen her, like some lovely wood sprite—which she might be, in this increasingly astonishing new world.

SHE was on her knees beside the darkly mirrored pool, supported by the slender arms and hands that looked alabaster white against the mossy bank on which she pressed. She was smiling down at her own reflection in the water—the famous Psyche painting which Connor so well remembered, come to life!

He was afraid to breathe, much less to speak, for fear of startling her. But when she turned her head and saw him, she showed no signs of being startled. Slowly she smiled and got gracefully to her feet, the clinging white Grecian draperies that swathed her gently swaying in the breeze to outline a figure too perfect to be flesh and blood. It was accentuated by the silver cord that crossed beneath her breasts, as sparkling as her ink-black hair.

The Complete Margaret of Urbs

The Complete Margaret of Urbs The Black Flame

The Black Flame The New Adam

The New Adam Dawn of Flame

Dawn of Flame The Ideal

The Ideal Proteus Island

Proteus Island The Worlds of If

The Worlds of If The Lost Master - The Collected Works

The Lost Master - The Collected Works The 27th Golden Age of Science Fiction

The 27th Golden Age of Science Fiction A Martian Odyssey

A Martian Odyssey Valley of Dreams

Valley of Dreams The Point of View

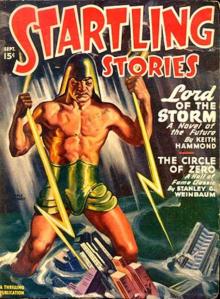

The Point of View The Circle of Zero

The Circle of Zero